Faculty convos: Economics and LAE

Sitting down with Dr. Brian Peckham to talk about his field

Dr. Brian Peckham is one of the longest-serving faculty members at UW-Platteville. Peckham began his teaching at UW-Platteville in 1987 and, including five years at University of Utah beforehand, has been teaching at the university level for 39 years.

I sat down with Dr. Peckham to discuss some of his teaching experiences through the years, what keeps him going and what he sees for the future.

First and foremost, Peckham addressed his age.

“People say, ‘well, what is an old dog like you doing still teaching? You ought to retire,’” Peckham chuckled. “Why retire? I’m having fun. Part of the fun involves trying to figure out what I should say in my classes and how to get that across to my students.”

Peckham included a caveat, though: although he is old enough to retire, he does not need to retire due to health concerns or family concerns, which is a valid reason for people to retire.

“There’s something else that marks a big difference between 1987 and today. Yes, we didn’t have Xerox machines, we didn’t have internet or email, but we also had more courses, at least in economics.”

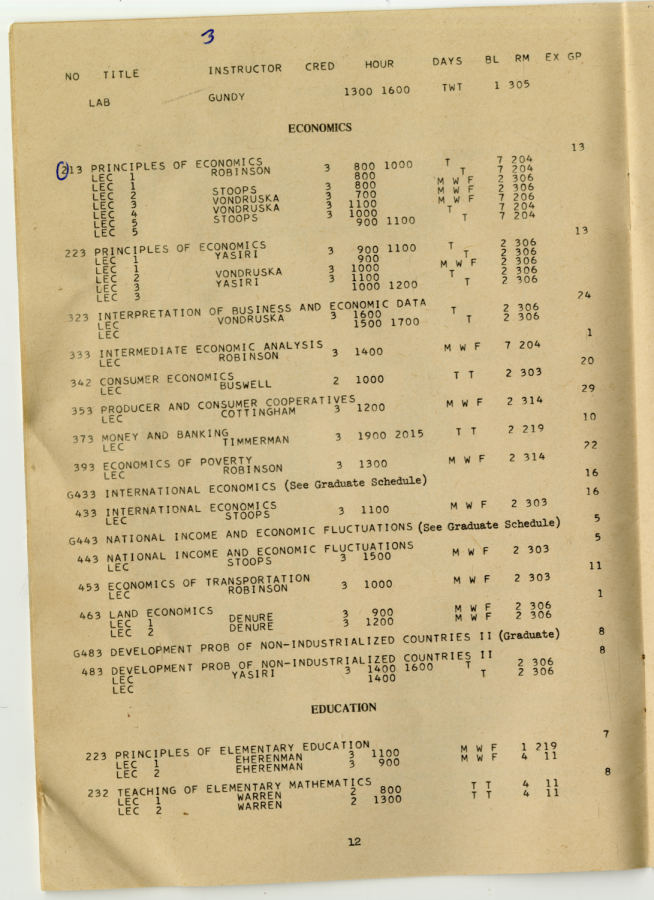

Peckham shared with me a class schedule for the second semester of 1965 – 1966 to illustrate the breadth of the university’s programs. I have scanned the page for the Economics classes, which operated from the Business Administration-Economics Department at the time.

“When I came here, we had seven people teaching in the economics department. We had courses in labor economics, international economics, money and banking, and all that. Now, today, in 2021, we’re down to one or two courses in Economics.”

Peckham continued, “The same thing has happened with History, same thing has happened with Sociology. Something that I have seen in the last 34 years is a shrinking and diminishing of the liberal arts, and that troubles me.”

Here, Peckham notes that the history of UW-Platteville as an educational institution has been that of one that educates miners, engineers, and scientists where the liberal arts may not be seen as paramount or essential. He emphasized his point by saying:

No matter what field you go into, you can benefit from a liberal education and from having courses in economics, history, philosophy, and literature. A liberal education can help you achieve personal growth, it can make you more original, make you more of an individual. It can strengthen your imagination and strengthen your resources against fear and despair. This is going to sound really strange to some students, but bad news up the road: as you get farther into life, you find that there are all sorts of threats blocking your progress and all sorts of reasons to give up hope, all sorts of reasons to despair about not only your future, but the future of American society, if not humanity.

On top of giving us “protection against hopelessness,” engaging in a liberal education also provides us with a plethora of historical figures from whom we may learn and grow. Peckham describes these people as moral exemplars.

“[Moral exemplars] are heroes who can inspire you. In my case, one of my moral exemplars is John Stuart Mill, the great British philosopher and economist in the 1800s. When I experience despair, I think: ‘You know, Mill also had those moments.’ He knew he was dying of tuberculosis; he knew in his lifetime that he would not be able to realize all of his ambitions for Britain.”

John Stuart Mill was an advocate for feminism, striving to find legal equality between men and women in Britain, which included trying to advance the cause of women’s suffrage. Mill was also one of the leaders in preventing Britain from allying with the Confederacy in the American Civil War. Because of these noble causes, Mill became a role model for Peckham.

Peckham emphasized another point: in our lives, we will experience encroachments against our problem-solving, thinking and decision-making by people who want us to see “only one way.” Liberal education, as Peckham describes, frees us from this possible dominance and enables us to broaden our capacity to think.

In the realm of economics, “Some people will want you to think there is one economic story that makes any sense, and they are the one telling it, and that you should vote for them … one thing I try to get across to my students is that’s just wrong. There is no ‘golden model’ that is the absolute truth.”

While no “singularly true” model exists, impartial, untrue and false arguments exist, and Peckham stressed the weight of sifting through the differences between a sound argument and sophistry, which consists of bad arguments and fallacies. Once more, an excellent place of practice is liberal education.

This handful of principles – resilience to despair, continued learning, diverse thinking – continue to influence Peckham’s teaching style as he reflects:

As I look back, both at my years at Utah and first couple of decades here, I am sorry that I didn’t do a better job for my students. I shudder when I think about some of the wretched courses that I inflicted on students… I want to stress that although my courses now are still far from perfect, I think they are better… in my experience, learning is possible. We can – this is one of the most noble features of human beings – discover our errors and through experience and discussion, try to rectify them.