16th Annual Ebony Weekend

Last Friday and Saturday, the UW-Platteville Black Student Union virtually hosted the 16th Annual Ebony Weekend conference.

The weekend began with an opening statement from BSU President Bassirou Toure and a recorded message from Chancellor Shields.

At 6 p.m., the first keynote speakers joined the Zoom conference. Nyle Fort, who introduced himself as a minister and Ph.D. student at Princeton University, was joined by Angela Harrelson and Selwyn Jones, the aunt and uncle of George Floyd. Both Harrelson and Jones have been speaking around the country ever since their nephew was killed, spreading awareness and working to fight racism and oppression.

“I will not let his death be in vain,” said Jones.

Fort, Harrelson and Jones all shared the respective moments they learned of Floyd’s death. Harrelson and Jones spoke about who Floyd was as a person, sharing their memories of him and the story of his life so as to keep his memory alive.

Fort explained how George Floyd’s life is “a microcosm of Black life in America,” as he faced poverty, racism and incarceration.

“He wasn’t perfect, but the thing is, he was a human being,” Harrelson said.

Harrelson heard about Floyd’s death the day after when a news reporter called her to get a comment. She didn’t even know he had been killed until she saw him on television calling for his mother.

“All I know is, no one could tell me the right answer,” Harrelson said.

“You’ll never forget about the day you heard about George Floyd,” Jones said.

Fort assured the audience that he, along with Harrelson and Jones, will make sure people don’t forget so that they know to remember.

“We don’t do it so we bury ourselves in a grave … we don’t let death have the last word,” Fort said.

Harrelson and Jones both testified that it is their duty to keep Floyd’s name alive and push for change. Fort closed by telling the audience that the only way for America to go forward is for Americans to work to understand the country’s problems and actively respond to what they learn and see.

“Our response needs to be as dramatic as our analysis,” Fort said.

In the morning of Feb. 27, President Toure split the audience up into two breakout sessions for the next two keynote speakers. After about an hour, the audience of each room switched to hear the other keynote speaker’s presentation.

Jacqueline Hunter, who is director of the Multicultural Family Center in Dubuque and an adjunct history professor at Divine Word College, presented on The Great Migration, which is the massive migration of Black people to the Northern U.S. throughout the 1900s all the way up to the 1970s.

Hunter explained how sharecropping, which became a way for White people in the South to maintain control

over Black people, often kept Southern Black families severly indebted. She also explained how the fear of lynching pushed Black people North.

Hunter spoke of push-pull factors, explaining how the Northern industrial labor shortage caused a need for unskilled laborers, and newspapers advertised success in the North as well.

Hunter also explained how important Black-owned newspapers were in offering perspective, talking mostly about the Chicago Defender, a Black-run newspaper which was distributed nation-wide.

Hunter clarified that racism in the North was as profound as in the South, but the ads circulated to Black Southerners offered more options. Black Southerners moved by train, boat, bus, car and more, and it was a long, grueling journey.

“Getting to the promised land did not come cheap,” Hunter said.

Hunter encouraged all Black students in the audience to share their families’ migration stories, conversing with them about their families’ histories.

The second keynote speaker, UW-Platteville associate professor David Gillota, presented “The Horror Film and The Black Experience,” beginning by explaining how representations in horror films can reflect larger social anxieties.

“Representations tend to shape our culture’s ideas about people,” said Gillota.

He shared the example of the radioactive monster trope in 50’s Japanese cinema. This trope represented the anxieties of society after the nuclear bombings of World War II.

Gillota started with early representations of Black people in media, explaining how Black characters were usually either part of the horror or the comic relief.

He mentioned George Romero’s zombie movie, “Night of the Living Dead,” which was one of the first films of its kind to portray a Black character as a strong protagonist. Romero continued to place Black actors in lead roles, although this did not catch on within the larger movie culture of the time.

Gillota moved to “blaxploitation,” explaining how horror movies would be exploited to target Black audiences, as Black people in America statistically enjoy horror films.

Gilotta then explained how Black people are portrayed in contemporary horror films, pointing out that modern horror movies often contain social commentary and portray society as the monster.

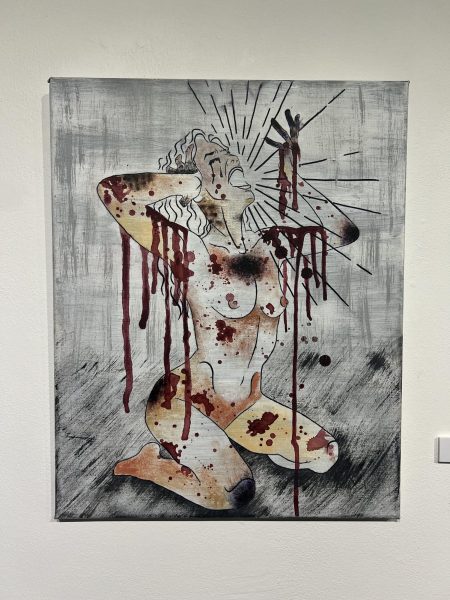

After a lunch break, the last keynote speaker of the weekend, Sakara Wages, presented on living authentically.

Wages is a fourth-year Ph.D. student at UW-Madison School of Social Work and a Critical Social Work scholar.

Wages began by clarifying that her talk centers Black people and their needs. She also explained that she uses the language that best allows her to express herself, does not code switch, uses AAVE and cusses.

“I recognize that some may feel uncomfortable, and that’s okay. Sit with that. Growth follows comfortability,” Wages said.

Wages defined code-switches as “the process of multicultural individuals using more than one language in conversation or other communicative acts.”

Wages explained that code-switching involves changing from one way of speaking to another between or within interactions. This includes accent, dialect and language.

“In my experience, code-switching encourages self-policing internal dialogue,” said Wages.

Wages asked the Black people in the audience if they feel obligated to code-switch in White spaces, to which 82% of the audience replied that they do sometimes feel this way. When asked if they do code-switch, 55% replied that they always do.

Wages supports authenticity, Black autonomy and freedom from external control or influence as means for liberation, or freedom from limits on thought or behavior. She encouraged Black audience members to live more authentically and avoid code-switching.

Wages provided some examples from her own professional life of times when her authenticity benefited her.

“Expressing your Blackness is revolutionary,” said Wages.

Her specific message to Black UW-Platteville students is to invest in themselves, talk to people in a position to help them and divest from White mental health systems, as White mental health systems generally fail to understand Black mental health and struggles.

Ebony Weekend ended on Feb. 27 with a recorded performance from Step Afrika, as well as a virtual visit from some members of Step Afrika who taught the audience some step moves.